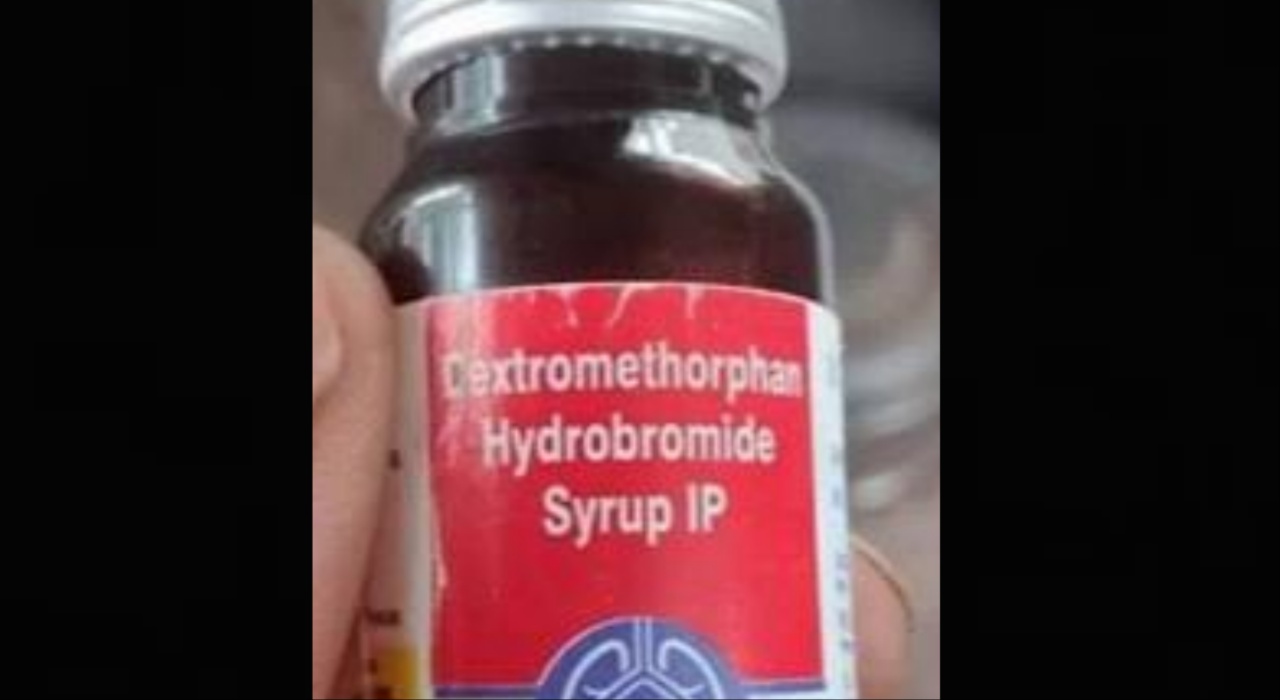

In Madhya Pradesh, 20 children have died and seven more are fighting for their lives after consuming a toxic cough syrup that should never have reached them. What began as a few mysterious deaths in Chhindwara has now exposed deep cracks in India’s drug safety system, one that is supposed to protect lives but instead failed them completely.

By September 29, 10 children had already died after taking Coldrif, a cough syrup made by a Tamil Nadu-based pharmaceutical company. Yet, even as deaths mounted, the response from state authorities was shockingly slow and careless.

Samples sent by regular post, no urgency

The most shocking part of the investigation is how crucial samples of the syrup were sent to the state’s drug testing lab, by ordinary registered post, the same kind used to send letters. There was no special courier, no emergency handling, and no tracking system, according to a report by NDTV.

While time was critical, it took three days just to send the samples from Chhindwara to Bhopal, a distance of barely 300 km. Every hour mattered, but the system moved at the pace of bureaucracy.

Even before test results arrived, Madhya Pradesh’s Health Minister Rajendra Shukla publicly declared, not once, but twice, on October 1 and 3, that the syrup was safe. Those words now stand in painful contrast to the grieving families who had already lost their children.

Tamil Nadu acted fast, MP delayed

In complete contrast, Tamil Nadu’s drug authorities acted immediately. Their testing lab checked the same syrup and within 48 hours confirmed that it was toxic. The state promptly banned its sale.

While Tamil Nadu was moving fast, Madhya Pradesh’s samples were still stuck in the postal system. By the time Madhya Pradesh banned Coldrif on October 4, more than two weeks had passed since the first child’s death. The delay proved fatal.

Early warnings ignored

The first alarm was raised on September 19, when reports from Nagpur suggested a possible link between contaminated cough syrup and child deaths. By September 22, state health teams had reached Chhindwara. Experts from the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and the National Health Mission (NHM) visited between September 26 and 28.

As per NDTV, samples were collected, and a temporary ban on Coldrif was imposed, but only in Chhindwara district. The syrup continued to be sold in nearby areas for days. On October 1, the Centre warned about two suspect syrups, Nastro-DS and Coldrif, and two days later Tamil Nadu confirmed Coldrif was unsafe. But by the time Madhya Pradesh reacted, the damage was done.

Collapsing drug testing system

The tragedy also revealed how weak and outdated Madhya Pradesh’s drug testing infrastructure is. The state has only three drug laboratories, in Bhopal, Indore, and Jabalpur, that can test a total of about 6,000 samples a year.

Currently, over 5,500 samples are pending, and each test takes two to three days. There are just 80 drug inspectors for the entire state of 50 districts. Officials quietly admit that, at this pace, clearing the backlog could take a year or more.

Madhya Pradesh’s Drug Controller, Dinesh Srivastava, admitted to NDTV that sending samples by post is “routine practice.” He added that in emergencies, samples should be sent by special carrier — but that “did not happen in this case.” Some officers have since been suspended.

Unused testing vans gather dust

Adding to the negligence are two mobile drug testing vans that could have helped identify contaminated medicines quickly. These vans, parked at the Food and Drug Administration compound in Bhopal’s Idgah Hills, have not been used for years.

One van hasn’t moved since 2022, and the other has never been used at all. When asked why, Joint Controller Tina Yadav said, “Some basic tests can be done in the van, but full analysis requires heavy equipment. It’s under consideration.”

These idle vans, meant to detect exactly such dangers, now stand as symbols of how bureaucratic delay can cost lives.

Now, the real question stands: Can the state fix its drug control machinery before another tragedy strikes?